Wheeler Ranch and Star Mountain

Easter, 1970, at Wheeler's Ranch. I am

playing an acoustic bass guitar made of

a Fender electric bass neck grafted onto a twelve string

guitar resonating chamber.

Photo (c) Sylvia Clarke Hamilton

Surely some of the happiest times I can remember were my early years at Wheeler Ranch, before my book was published. Everything I am, I expressed abundantly--drawing, writing, singing, songwriting, gardening, practicing yoga, walking far, loving deeply, communing with children, forming lifelong friendships, attending and creating community gatherings, reading books and passionately discussing what I had read, preparing meals, sewing, bathing in hot springs and the community sauna dome, making ensemble music, and, especially, savoring the sounds, sights and smells of the forest where automobiles did not go--at dawn, at dusk, at night. I knew the constellations, the bird calls, the names of the plants along the trail. I was not prone to poison oak, and I felt comfortable naked in fifty degree weather and in mixed company.

About one hundred people lived on Wheeler's Ranch in those days, although, most days, walking the land from end to end, one was unlikely to encounter even ten. We lived in small structures hidden in the woods, and followed our highly individual pursuits. I liked to work in the large community garden, but many households included their own vegetable gardens. On Sundays, we gathered for a community potluck and music jam--guitars, hand drums and flutes, usually being played in several different keys and time signatures. After the summer fire season ended, the Sunday gathering often included a sweat lodge, created by heating stones in a bonfire, and, once the fire burned low, lifting the stones on pitchforks and placing them in the central pit of a dome that was insulated with army blankets and plastic tarps, and carpeted with straw. We squatted naked in the sweat lodge, tossed cupfulls of water of the rocks, and rubbed our bodies with fragrant bay leaves. I liked to sing in the sweat lodge, and eventually took my name from the cleansing herb I associated with those ecstatic baths.

1970. Making music in front of the

Sonoma County Courthouse. When Living On The Earth

was published,

I threw a three-day, eight-hundred-guest party on the

land. A week later the police raided us, claiming to be

in hot

pursuit of a San Quentin escapee. They arrested a few

people; eventually the bust was thrown out of court,

but not before I posted bail for my friends. I am wearing

a striped djellava given to me by Jean Varda.

Karin Lease, in whose living room I

have roosted since June 9, was one of my

favorite hang-out buddies at Wheeler's. We both loved

needlework. We relished

our discovery that girls could pee standing up, too--without

even stopping a conversation.

Fog drifts over the ridge from the sea. Some things do not change.

Today I drove out to pay a call on Bill Wheeler and see what was going on at the land. I stopped along the way in the tiny town of Occidental to mail packages, and noticed a town flag on the back wall behind the post office counter, on it a pine tree, a plate of spaghetti, a sheep and a peace sign. "That sums up Occidental," I remarked to the postmistress, "sheep ranches, evergreens, hippies, and three Italian restaurants." "Yep," she replied, "sure does."

By sheer coincidence, in walked David Hatch, my old friend who still lives at the Ranch, who had not been off the land in two weeks and was on a mail and grocery run. We agreed to meet at the parking area of Oceansong, the commune above Wheeler's, through which one must pass to get to the Ranch. From there, I rode down to the ranch with David and two friends in an old lowrider car, scrunched up in the backseat amid packs and packages, pretty much as I did in the days when I used to hitchhike.

Downtown Occidental, originally settled by Italians who built the Occidental Railroad.

On the eve of his sixieth birthday,

Wheeler is becoming

famous in the Bay Area for his oil paintings. Behind us

is the house he handbuilt with its wonderful stone

chimney.

Bill and I reminisced over his album of old photos, and he allowed me to borrow and scan the three historic photos at the beginning of this page, none of which I had ever seen before. Raspberry Sundown Hummingbird Wheeler, the daughter I watched being born in Bill's vegetable garden is now Jessica Wheeler, a software magnate in San Francisco who birthed her child in a hospital. Bill laughs and enjoys the irony. I loved the contrast of Bill's weathered handmilled wood and hand-set stone home with the ancestral antiques that followed him from his upbringing as the heir of the Wheeler-Wilson sewing machine company.

That's one of the old family sewing machines on the carved chest on the left.

A corner of Bill's studio

Here, from the Diggers' web site, are Bill Wheeler's reminiscences of first meeting me and what transpired afterward:

"Round brown eyes, round young body and round curly brown hair, Alicia spoke softly but with assurance. After thinking quietly for a while, she asked me if I knew of any coffee houses where she could play and sing for money. Shortly before dark, she dressed warmly and set out to find a place to stay. My concern over her welfare that rainy night was unfounded as I discovered a few days later when she returned to the studio, bursting with merriment, and related her adventures. She had been welcomed at several people's houses and was planning to go back to the city, get her things and come back to stay.

"Gray weeks passed before I saw her again. This time, Alicia wore the air of an established resident and nothing else. When most folks were still in warm sweaters, Alicia could be seen wandering around in the fog without a stitch of clothes, a book or some sewing under her arm. When the sun began to warm the air the following spring, she was in the garden almost every day, doing yoga and tending the vegetables. She was the only community member who gardened regularly that second summer. Without her care, the community garden would have never started. In those days she was also the only person on the Ridge who was neither 'without income' nor on welfare. She generated income from various creative projects which she sold, an activity then unique among Open Landers.

"Alicia began working on an intercommunal newsletter, describing in unpretentious script and with simple line drawings the basic skills needed by newcomers to live primitively in an isolated, rural community. She demonstrated with childlike fluidity how to build a shelter, shit in the ground, chop wood, have a baby, etc. The project took her over a year, during which time she left with the winter '69 exodus that took many Ridge residents further north into Humbolt County.

"When she returned the next summer, she announced that the newsletter had grown into a book which was being privately financed and published by a Berkeley publisher with the title Living On The Earth. It turned out to be a phenomenon, the first edition of 10,000 selling out in three weeks. One copy found its way to Bennett Cerf at Random House. Delighted and impressed, Cerf bought the book and Alicia, now Alicia Bay Laurel, was sent on a national promotional tour to explain to America the joys of Open Land living. By the following Christmas, Living On The Earth had become a best seller with 150,000 copies sold. It engendered much sympathy and interest in a simple, non-technical life style. Whatever it was we were doing together on the land, people were hungry to know more."

I found a quote of mine from these times on lightlink.com: "Let's all go out into the sunshine, take off all our clothes, dance and sing and make love and get enlightened!"

Bill and I talked over lunch, but he had to hurry off to buy victuals for his birthday bash, so I set out on a walk around the land to look for clues of what I once knew.

Not far from Bill's house stands a

sweat lodge, complete with fire pit and

hand lashed poles, much like the structures illustrated

in Living On The Earth.

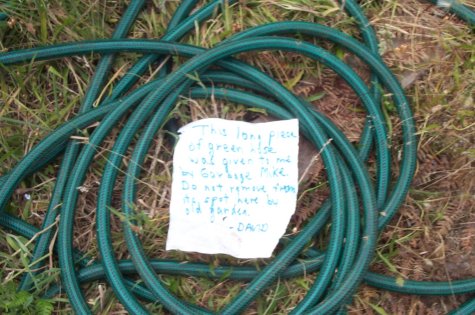

Note reads: "This long piece of

green hose was given to me by Garbage Mike.

Do not remove from this spot here by old garden. David"

Garbage Mike, one of the first dedicated

environmentalists of my acquaintance

has always been generous in helping to preserve the land.

The old garden, however, does not look much used.

Downtown Wheeler Ranch: the crossroads by the old community garden

"It's pretty boring here now," David Hatch tells me. "No Sunday potlucks. No one goes naked except me, and I only go naked at home. There are only twelve people here and we never see each other. Everyone does their own trip." David's trip is meditating, with occasional forays into cyberspace on the Ranch's intermittantly working computer, which is up by the front gate in the only shack with both telephone and electricity. David worked as a computer technician back in the days of the big mainframes, before he dropped out, and only recently started catching up with personal computers. He says other residents occasionally use the computer, but they invariably fail to shut it down properly when they are through using it.

David Hatch outside the community

computer shack. The TV is part of a

series of outdoor sculptures created by "one of (artist

and resident) Wilder Bentley's kids."

Near the back of the land, a trail off the main road leads to a house hidden in the trees.

Baby fir trees planted in the early

'seventies

tower above the road to the back of the land.

At the back of the land, the dense

forest suddenly ends.

On the neighbor's land, only pasture faces the sky.

David's house snuggles under an oak

tree, the green tarp a concession to heavy

winter rains and an unevenly built roof. I am the first

guest to visit in months.

David walked with me up the dirt road through the neighboring commune to where the Peugeot was parked. We were stopped by a young woman in a pick-up truck who said she worked for the census bureau. Apparently in two months of questioning, no one had disclosed the number of residents on the land. She was concerned that if the census bureau was not informed by tomorrow, Wheeler would be fined. She wanted to help. David did not. He suggested she contact Bill by telephone. I sensed that it was not about paranoia, but more a resistence to being a statistic. Hermits do not fit into molds.

I drove over to Star Mountain, the commune I inadvertedly started by looking for a house with electricity inwhich to practice music with my bandmates from Wheeler Ranch. Bill Wheeler offered to lease me the two-hundred-and-fifty-acre five-armed ridge directly west of Wheeler Ranch. I suggested the name based on the topography. It stuck, but I didn't. Many others did, and, thirty years later, it is still going.

Long-time resident Karen Smith, with her husband, organic farmer Michael Smith, and their three children, were moving into what had been the community house, the original structure on the land. She said that there are thirty-three current residents at Star Mountain, fifteen of whom are under ten years old. She had just spent weeks rescuing the main garden from utter ruin. It looked lovely.

Karen Smith, her youngest child and her dog in the refurbished community garden.

The center of all sustainability at

Star Mountain

is the garden of Phyllis Hughes, which includes

orchards, circubits, greens and flowers. "It's a

passion with me," she glowed. She gathered Thai

basil,

cabbage, carrots, cilantro, mint, and garlic, and

prepared a batch of Thai springrolls with peanut sauce.

With her husband Tom's old guitar, I serenaded her while

she cooked.

Carol, a friend from the remote town of Covelo, joined us

soon

after, and we laughed together for a couple of hours that

night.

Tom Hughes built this house of lumber

he milled, and much of the furnishings

are handcrafted by Phyllis. The fog obscures "the

world's most fabulous view"

(per Phyllis, and I take her word for it), but the house

exudes charm and peace

even without the view of Mount Tamalpais and the forested

valley below.

A much younger Tom is in the 1970 courthouse grouping

above:

he's the last person on the right side of the photo, and

one of the first to move

to Star Mountain. The woman standing nearest to him is

Mary Garvin

a close friend at the Ranch and ever after, with

whom I will be driving from New York to Colorado.

Phyllis and Tom sleep beneath a

handmade roof and a handmade quilt

looking out over the land upon which they hope to live

the rest of their lives.